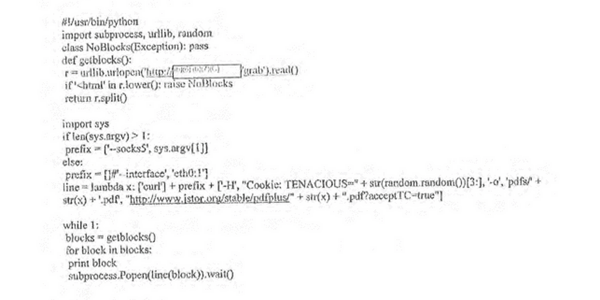

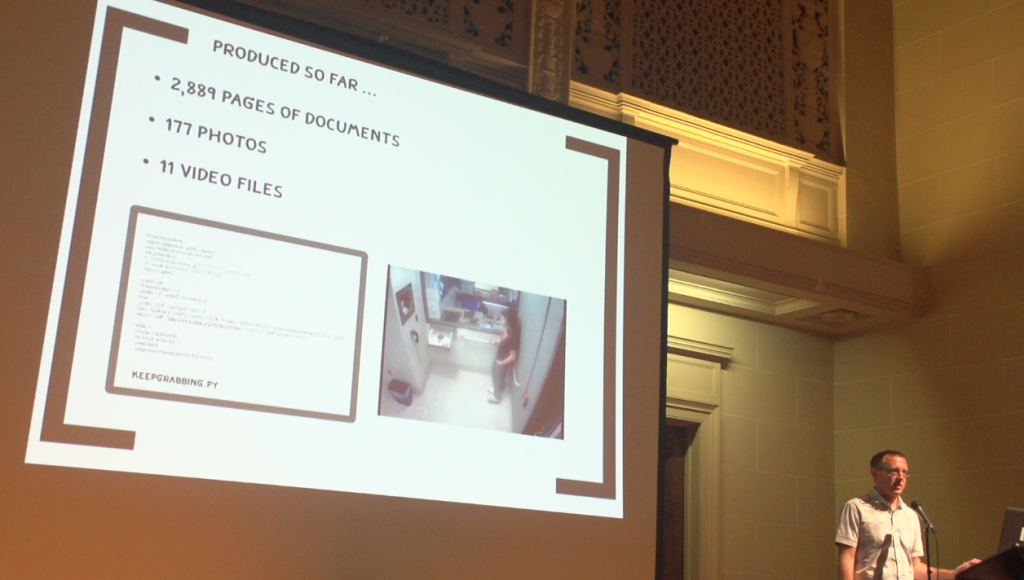

The recent article by The Intercept, and Wired‘s coverage of The Intercept‘s announcement, told us that Securus, a prison phone company here in the U.S., had been hacked, and that the hacker then uploaded the data obtained to The Intercept via SecureDrop.

It really provided a perfect example of a whistleblower releasing information in order to help the common man. In this case, assisting inmates and their families by drawing attention to:

1) Their sensitive data not being stored properly.

2) Recordings of attorney-inmate “privileged” calls that should never have been recorded.

3) “Kickbacks” the government agencies awarding the phone contracts were getting that these families were funding with their overcharged calls.

This article provided me with a real world example for my movie, “From DeadDrop to SecureDrop,” which was pretty exciting, because I had originally given up hope on having a real world example, mainly because there are lots of different reasons why it often might not be in the whistleblower’s best interest to make any of the details surrounding any one particular leak public. (Mainly out of fear of releasing information that could potentially identify the whistleblower, especially if they were an insider.)

In this case though, although Securus is claiming that it was a leak from an insider, rather than a hack (see the bottom of The Intercept article), the folks at The Intercept make it pretty clear in their article that they believe it to be a hack, saying “an anonymous hacker who believes Securus is violating the constitutional rights of inmates” uploaded the data.

It appears that, of the 70 million records, at least 14,000 of these calls were made by detainees to their attorneys, and therefore should NOT have been recorded. However, although most legal experts agree that Securus has violated those inmates’ rights by recording those calls, it’s hard prove and calculate damages, should an inmate choose to challenge it. The burden is on the inmate to prove that such improperly recorded calls were also accessed by a prosecutor and then resulted directly in some kind of damage to the inmate (for instance, a longer sentence).

But as The Intercept article explains, prosecutors are not always forthcoming about accessing such calls. For example, in a lawsuit brought by the Austin Lawyers Guild, “four named attorneys, and a prisoner advocacy group … alleges that”:

“…despite official assurances to the contrary, privileged communications between lawyers and clients housed in the county jails have been taped, stored, “procured,” and listened to by prosecutors. The plaintiffs say that while some prosecutors have disclosed copies of recordings to defense attorneys as part of the regular evidential discovery process, other prosecutors have not, choosing instead to use their knowledge of what is in individual recordings to their “tactical advantage” in the courtroom “without admitting they obtained or listened to the recordings.”

Over the last few weeks we’ve all learned how Securus, GTL, CenturyLink, Telmate, NCIC and other companies overcharge prison inmates for calling their families. But to learn, via a Prison Legal News article from 2011, referenced in The Intercept article, that the overcharging was specifically to pay “kickbacks” to the prison executives that awarded the contracts, and that this had already been written about extensively for many years, kinda blew my mind.

So what’s Securus’ side of the story? A Securus Press Release from October 2014 seems like it was published in order for Securus to make it clear to its government agency clients that it tried to keep the commission system alive. Although it’s hard to believe the release made it out of the company’s PR department, with statements like:

“We have been a vocal advocate of maintaining commissions and have spent approximately $5 million in legal fees and other costs on behalf of our facility customers over the last decade to maintain commissions, but the FCC maintains that it is not good public policy to have the poorest in society help to fund government operations, even though the programs funded are worthwhile.”

The press release also has Securus’ CEO giving an explanation regarding where the money from the overcharges is going:

“Part of the heritage of our business is that we calculate, bill, and collect commissions and pay those to jails, prisons, and local, county, and state governments,” said Richard A. (“Rick”) Smith, Chief Executive Officer of Securus Technologies, Inc. “Clearly these commission payments that have been used to fund critical inmate welfare programs and support facility operations and infrastructure have improved the lives of inmates, victims, witnesses and individuals working in the correctional environment, and helped to fund government operations. And it appears, sadly, that regime may come to an end in the not too distant future,” said Smith.

This quote suggests that money from the overcharges benefits the prisoners, in the long run. But this raised even more questions in my mind. Why are prisoners’ families paying for their own “facility operations and infrastructure” costs? As addressed in the interview with Alex Friedmann, it turns out that the budgets these overcharges go into have little or no government oversight, be they at the Local (Municipal), State, or Federal level.

I contacted Alex Friedmann, Managing Editor of Prison Legal News, to get some answers. Prison Legal News has reported on criminal justice-related issues since 1990 and is a project of the Human Rights Defense Center.

Lisa: Let’s talk about the SecureDrop upload that was announced on November 12th. What were your first impressions, when you read about the upload?

Alex: It wasn’t terribly surprising. Nor was it surprising that they were apparently recording attorney-inmate calls. There are already some lawsuits in Texas and other places over these issues. Although the volume of recorded calls was somewhat surprising.

Really, the most surprising thing was that somebody actually cared enough to release the records. That was rare, that someone decided this was an issue, and decided to do it, and did it.

Lisa: What do you feel is the takeaway on this?

Alex: The important thing about the SecureDrop dump was that it showed what data was being collected, and that it’s not being stored securely.

Storing such sensitive data insecurely is a privacy violation. Much in the same way that Target was responsible when all the private data of its customers was released, due to not being properly protected. For this reason, it doesn’t matter whether the leak came from inside or outside; the sensitive data was not being properly protected. Securus claiming it was an insider, and not a hack, doesn’t explain away this issue; their data was still insecure.

Lisa: Let’s talk about the attorney-client privilege issue. It looks like at least 14,000 of the phone calls recorded “shouldn’t have been.” So, walk me through this. A call is “improperly recorded,” lets say as a result of recording a call to a number on “the list” of attorney numbers (that should therefore not be recorded). Could you explain why you think that it would be hard for an inmate to show they were harmed by these calls being merely recorded?

Alex: Okay. So the onus is on the prisoner to prove that 1) the call was accessed by a prosecutor and 2) that the prosecutor acted on the information that was heard in those phone calls, and then used that information in some way harmful to the prisoner. To show damages, you’d have to show that the prosecutor listened to the call, and then took action based on that call, and that doing so resulted in a longer sentence, or something else adverse directly happening to the prisoner as a result.

Lisa: So, at that point, it would have interfered with the prisoner’s 6th Amendment “Right to Counsel?”

Alex: Yes. But they would have to show injury. Though there can be injury in the form of chilling their right of access to counsel, if they know that calls to their attorneys are being recorded.

Lisa: So, moving forward, post-upload. Now that the fact that these calls were being improperly recorded, there could be a chilling effect, but for calls that took place before the upload, the argument would be “how could their speech be chilled if they didn’t know they were being recorded?”

Alex: Correct. In effect, it’s like giving officials one free bite at the constitutional apple. They’re not supposed to record attorney-client phone calls, but if they do, it’s hard to hold them accountable.

Lisa: Let’s talk about the “kickbacks. These “kickbacks” have been reported on for years, without anyone doing anything about them?

Alex: Well, yes. Because it may be that no laws are actually being violated, due to general lack of accountability of these programs. There tends to be a lot of “wiggle room” in prison and jail budgets and very little oversight. The practice of prison phone service providers giving kickbacks to corrections agencies – up to 94% of gross revenue in some cases – is perfectly legal. And that’s the problem, that it’s legal.

Lisa: Is this happening primarily at the local (Municipal), State, or Federal level?

Alex: When we talk about prison and jail phone “commissions,” in general, we are talking about a multi-level, local (municipal), state, federal commission kickback model that exists at all three levels.

Lisa: Why is it so hard to follow the money?

Alex: Oh you can follow the money, it’s just that there is little actual oversight of the budgets themselves, and few regulations defining allowable expenditures in most cases.

Lisa: So no one’s checking that it’s spent properly, and no one defining what “properly” is?

Alex: Yes. Due to the way the money is mixed up in the funds. It’s all mixed up and hard to track. Once it gets to something like a county’s general fund or a state’s general fund, its impossible to track completely. Once the money finds its way to the general budget of an agency. For instance, the Sheriff’s office. They can often do whatever they want with it.

Lisa: Please explain how, once the money goes into something called the IWF (Inmate Welfare Fund), you can put in a “public records request,” and get a breakdown of what went in and out.

Alex: For a number of years we have submitted public records requests to corrections agencies nationwide, and obtained copies of prison phone contracts, rate data and commission data, which are posted on our data site, www.prisonphonejustice.org. In some cases we have also requested records related to how IWF funds are spent; for example, at one county jail we found that IWF funds were used to pay for prisoners’ meals, as well as a variety of other things, such as server upgrades, that either do not benefit prisoners or should be paid from the jail’s general fund, not the IWF.

Lisa: So, it’s the position of the Human Rights Defense Center that there should be no commissions, no matter what the money is used for?

Alex: Right. Let’s say that most of the money from the excessive phone charges does go back into prisoner programs. So what? The state is supposed to be paying for prisoner programs, not the families of prisoners. Hence, our stance is that there should be no commissions. It’s not a question of what they should be spent on.

Overcharging the families of prisoners in this way would be like charging taxes for schools only on households with children. These services should be funded by everyone, because they benefit everyone. Just like schools, roads, and other public services. Similarly, programs and services for prisoners need to be funded through the general tax base. Otherwise, it’s a tax solely on prisoners’ families, which is unfair.

Lisa: In the Intercept article, an example is given of a couple deciding between phone time and food. It struck me that no one should have to make those kinds of choices.

Alex: Right, prison phone rates shouldn’t be much higher than anyone else’s phone rates. And if it costs more to make such calls “secure,” that should hardly be an expense that the families are expected to cover, any more than prisoners’ families should have to pay for razor wire, security cameras or guards’ salaries at prisons and jails. Again, incarceration is a public service and those costs should be paid by all members of the public, not just prisoners’ families.

Take the county jail I mentioned, where one can actually access the actual expenditures for the IWF funds, which were used to pay for food and server upgrades, among other things. Why are prisoners’ families paying higher phone rates to cover such expenses?

Lisa: Arguably, how do “server upgrades” help the prisoners directly anyway?

Alex: They don’t, unless you really stretch the language for how IWF funds should be used. But even for expenditures that do directly benefit prisoners, so what? Why are the prisoners’ families paying for things that should be covered by the corrections agency? These are the most basic of necessities that should be paid for by the prison system itself, not by the families of those being incarcerated.

The simple fact remains that prisoners’ families are being exploited and have been for some time, and that the various agencies (Bureau of Prisons, state Departments of Corrections) allow it to happen. This amounts to an estimated $460 million in phone commission kickbacks each year, as it involves not just state or federal prisons, but also immigration facilities, county jails and other detention centers. Nor does this address the many other ways that prisoners and their families are price gouged.

Lisa: A report from the FCC explains (on page 12, paragraph 23) that, although these unfair price hikes only represent somewhere between 0.3% and 0.4% of the budgets the money collected from them go into, “What appears to be of limited relative importance to the combined budgets of correctional facilities has potentially life-altering impacts on prisoners and their families.”

Alex: It depends on the agency and its budget, but in general, prison and jail phone commissions are just a drop in the government’s bucket of taxpayer funds. Yet prisoners’ families face real hardships when they have to pay inflated phone rates to stay in touch – money spent on calls could otherwise be spent on rent, food, healthcare needs, and so on. But what mother doesn’t want to speak with her incarcerated son? Or what wife wouldn’t take a call from her imprisoned husband? Keep in mind that prison and jail phone contracts are monopoly contracts; families have no choice and can’t choose a less expensive option for accepting phone calls from their incarcerated loved ones.

One of the main problems with all of these scenarios in which prisoners and their families are exploited is they have no voice in our legal or political systems. It’s easy for those in charge to take advantage of these families who have no one looking out for them or protecting their interests. Both prisoners and their family members are easy targets for greedy prison telecommunications companies and their government partners. There are currently around 2.2 million people locked up in prisons and jails in the United States, which means 2.2 million families are affected by these exploitive prison and jail phone rates.

The FCC has recently taken action on this issue, after more than a decade of efforts by advocacy organizations, including Prison Legal News/Human Rights Defense Center, but more needs to be done. The two largest ICS providers, GTL and Securus, are owned by private equity firms, and as such are only interested in financial returns, not fair and equitable phone rates for families.

Lisa: Would you say this whole scenario of having private companies, whose bottom line is profit, rather than servicing the needs of their customers, is just another example of why privatizing the prison industry is a bad idea – especially with little or no government oversight, which seems to always be the case?

Alex: Removing for-profit incentives from our criminal justice system would certainly help shift the focus away from providing various correctional services – including operating prisons and jails – for the purpose of making money. We tend to monetize almost everything in the United States, but I submit our criminal justice shouldn’t be included. That being said, our public corrections agencies aren’t that great either; the entire system is in need of reform, from the top down.

Lisa: But you think prison and jail phone rates will be going down, for sure, next year?

Alex: The FCC order has already been issued. Once it’s published in the Federal Register, it will go into effect after 90 days. So that’s a done deal, though ICS providers will likely challenge it in court. Thus, there is no guarantee the rates will go down on a date certain, but eventually they will go down.

Lisa: So the big question is “what can prisoners and their families do to protect their privacy, now that they know calls are being recorded, and perhaps stored for months or years into the future? And insecurely?

Alex: They, through their elected lawmakers, need to demand accountability from the prison and jail officials who enter into contracts for phone services, to ensure their privacy interests are respected to the same extent as all other citizens.

There isn’t much families can do right now to make things better, particularly with respect to privacy. There is a combined class-action suit pending against GTL, but it doesn’t focus on privacy issues. They could complain to their state Public Utility Commission (or similar agency that regulates in-state phone services). In many states, the telecom industry has been deregulated, however. But really, how does anyone protect their privacy given that our own government spies on its citizens through the NSA?

References:

1. Not So Securus – Massive Hack of 70 Million Prisoner Phone Calls Indicates Violations of Attorney-Client Privilege

November 11, 2015. By Jordon Smith and Micah Lee for The Intercept. https://theintercept.com/2015/11/11/securus-hack-prison-phone-company-exposes-thousands-of-calls-lawyers-and-clients

2. SecureDrop Leak Tool Produces a Massive Trove of Prison Docs November 11, 2015. By Andy Greenberg for Wired. http://www.wired.com/2015/11/securedrop-leak-tool-produces-a-massive-trove-of-prison-docs/

3. Nationwide PLN Survey Examines Prison Phone Contracts, Kickbacks. April 15, 2011. by John Dannenberg for Prison Legal News. https://www.prisonlegalnews.org/news/2011/apr/15/nationwide-pln-survey-examines-prison-phone-contracts-kickbacks/

4. Prison Legal News, Complete Issue, December 2013. https://www.prisonlegalnews.org/media/issues/12pln13.pdf

5. Securus Press Release, October 2014.

http://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/securus-provides-over-13-billion-in-prison-jail-and-government-funding-over-the-last-10-years-281105252.html

6. Securus Press Release, March 2015.

http://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/securus-provides-over-13-billion-in-prison-jail-and-government-funding-over-the-last-10-years-300043861.html

7. GTL on reducing rates (From October 2015):

http://www.gtl.net/global-tel-link-gtl-grave-concern-with-proposed-fcc-decision-on-inmate-calling-services/

8. Jail’s Inmate Welfare Fund Gets Rich .

http://www.independent.com/news/2014/sep/29/jails-inmate-welfare-fund-gets-rich/

9. From HRDC executive director Paul Wright, October 23, 2015, FCC Caps the Cost of Prison Phone Calls .

https://www.prisonlegalnews.org/news/2015/oct/23/hrdc-executive-director-paul-wright-october-23-2015-fcc-caps-cost-prison-phone-calls/

12. FCC Second Further Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, October 22, 2014. https://apps.fcc.gov/edocs_public/attachmatch/FCC-14-158A1.pdf

11. Authorities Listen in on Attorney-Client Calls at Jails in FL, CA and TX, by David Reutter for Prison Legal News. Aug. 15, 2008 https://www.prisonlegalnews.org/news/2008/aug/15/authorities-listen-in-on-attorney-client-calls-at-jails-in-fl-ca-and-tx/

12. Suit Filed Over Minnesota Jail’s Secret Recording of Privileged Phone Calls, by Matthew Clarke for Prison Legal News. April 15, 2009 https://www.prisonlegalnews.org/news/2009/apr/15/suit-filed-over-minnesota-jails-secret-8232recording-of-privileged-phone-calls/

13. Recording of Nashville, Tennessee Jail Prisoners’ Attorney Calls Criticized, published in Prison Legal News, Dec. 15, 2011. https://www.prisonlegalnews.org/news/2011/dec/15/recording-of-nashville-tennessee-jail-prisoners-attorney-calls-criticized/