This is a reference for our post about Aaron’s Pacer Project Explained.

This was published in the New York Times on February 12, 2009.

An Effort to Upgrade a Court Archive System to Free and Easy

By JOHN SCHWARTZ

FEB. 12, 2009

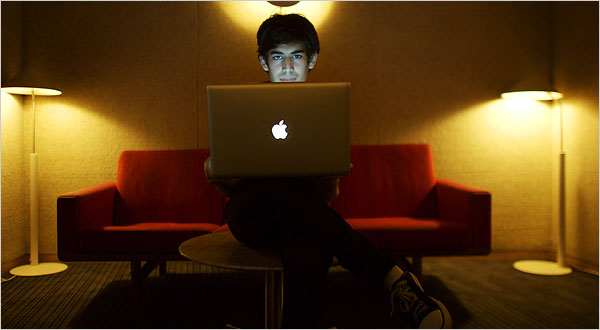

Aaron Swartz used a free trial of the government’s Pacer system to download 19,856,160 pages of documents in a campaign to place the information free online. Credit Michael Francis McElroy for The New York Times

Americans have grown accustomed to finding just about anything they want online fast, and free. But for those searching for federal court decisions, briefs and other legal papers, there is no Google.

Instead, there is Pacer, the government-run Public Access to Court Electronic Records system designed in the bygone days of screechy telephone modems. Cumbersome, arcane and not free, it is everything that Google is not.

Recently, however, a small group of dedicated open-government activists teamed up to push the court records system into the 21st century — by simply grabbing enormous chunks of the database and giving the documents away, to the great annoyance of the government.

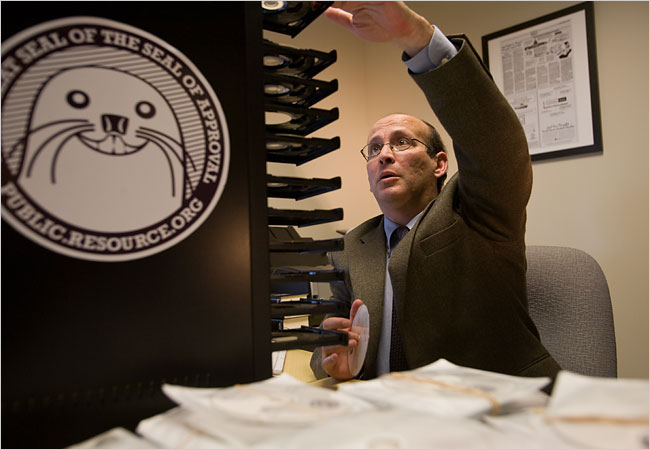

“Pacer is just so awful,” said Carl Malamud, the leader of the effort and founder of a nonprofit group, Public.Resource.org. “The system is 15 to 20 years out of date.”

Worse, Mr. Malamud said, Pacer takes information that he believes should be free — government-produced documents are not covered by copyright — and charges 8 cents a page. Most of the private services that make searching easier, like Westlaw and Lexis-Nexis, charge far more, while relative newcomers like AltLaw.org, Fastcase.com and Justia.com, offer some records cheaply or even free. But even the seemingly cheap cost of Pacer adds up, when court records can run to thousands of pages. Fees get plowed back to the courts to finance technology, but the system runs a budget surplus of some $150 million, according to recent court reports.

To Mr. Malamud, putting the nation’s legal system behind a wall of cash and kludge separates the people from what he calls the “operating system for democracy.” So, using $600,000 in contributions in 2008, he bought a 50-year archive of papers from the federal appellate courts and placed them online. By this year, he was ready to take on the larger database of district courts.

Those courts, with the help of the Government Printing Office, had opened a free trial of Pacer at 17 libraries around the country. Mr. Malamud urged fellow activists to go to those libraries, download as many court documents as they could, and send them to him for republication on the Web, where Google could get to them.

Aaron Swartz, a 22-year-old Stanford dropout and entrepreneur who read Mr. Malamud’s appeal, managed to download an estimated 20 percent of the entire database: 19,856,160 pages of text.

Then on Sept. 29, all of the free servers stopped serving. The government, it turns out, was not pleased.

A notice went out from the Government Printing Office that the free Pacer pilot program was suspended, “pending an evaluation.” A couple of weeks later, a Government Printing Office official, Richard G. Davis, told librarians that “the security of the Pacer service was compromised. The F.B.I. is conducting an investigation.”

Lawyers for Mr. Malamud and Mr. Swartz told them that they appeared to have broken no laws, noting nonetheless that it was impossible to say what angry government officials might do.

At the administrative office of the courts, a spokeswoman, Karen Redmond, said she could not comment on the fate of the free trial of Pacer, or whether there had been a criminal investigation into the mass download.

The free program “is not terminated,” Ms. Redmond said. “We’ll just have to see what happens after the evaluation.” As for the system’s cost, she said: “We’re about as cheap as we can get it. We’re talking pennies a page.”

Carl Malamud has been leading the effort to push the court records system into the 21st century. Credit Heidi Schumann for The New York Times

Meanwhile, the 50 years of appellate decisions remain online and Google-friendly, and the 20 million pages of lower court decisions are available in bulk form, but are not yet easily searchable. “I want the whole database in 2009,” Mr. Malamud said.

Mr. Malamud, 49, has a long record of trying to balance openness with privacy, and has also pushed the Securities and Exchange Commission and the Patent and Trademark Office to put their records online free. But the issue is a thorny one with court documents, which often contain personal information.

Daniel J. Solove, a professor at the George Washington University Law School, noted that marketers skim court records for personal data, and making records easier to troll will put even more data at risk. “It’s taking away this middle ground that offered a lot of protection, practically, and throwing it into this radically wide open box,” he said.

Newsletter Sign Up

Continue reading the main story

California Today

The news and stories that matter to Californians (and anyone else interested in the state), delivered weekday mornings.

You will receive emails containing news content, updates and promotions from The New York Times. You may opt-out at any time.

See Sample Privacy Policy Opt out or contact us anytime

But this argument for what is known as “practical obscurity” does not convince Peter A. Winn, a privacy expert who is an assistant United States attorney in Washington State. Noting that he was speaking only for himself, he argued that the courts developed rules over the last 400 years to protect privacy.

“It worked in the bricks-and-mortar age — it should work in the electronic age,” Mr. Winn said. The administrative office of the courts, he said, should take on the role of policing privacy on its databases. “This is going to take focus and a lot of hard work,” he said.

Mr. Malamud agrees that the court system needs to do a better job of protecting privacy. He found thousands of documents in which the lawyers and courts had not properly redacted personal information like Social Security numbers, a violation of the courts’ own rules. There was data on children in Washington, names of Secret Service agents, members of pension funds and more.

“They’re pretty spectacular blunders,” he said. He sent letters to the clerks of individual courts around the country. After some initial inaction, and repeated and increasingly spirited notices from Mr. Malamud, most of the offending documents were pulled from the databases to be redacted.

Ms. Redmond, of the administrative office of the courts, said the courts comb through the documents “on a regular basis” and tell lawyers to redact confidential information. The number of violations, she noted, was relatively small.

Mr. Malamud scoffed at that. “This is a large number of transgressions, and this is illegal,” he said. “The law doesn’t say that you should only publish a small number of Social Security numbers!”

Mr. Malamud said his years of activism had led him to set a long-shot goal: serving in the Obama administration, perhaps even as head of the Government Printing Office. The thought might seem far-fetched — Mr. Malamud is, by admission, more of an at-the-barricades guy than a behind-the-desk guy. But he noted that he published more pages online last year than the printing office did.

Mr. Malamud represents a perspective of openness and transparency that is much in tune with the new administration’s, said Lawrence Lessig, a law professor at Harvard who is a leading advocate for free culture. “The principles are those that Carl has been at the center of defining,” he said.

The idea also seems to have a measure of appeal for John D. Podesta, a longtime fan of Mr. Malamud and head of the Obama transition team, who stopped short, however, of anything resembling an endorsement. “He would certainly shake things up,” Mr. Podesta said, laughing.

Mr. Malamud says he is not counting on the new administration’s being quite that bold. Besides, he said, he keeps himself awfully busy doing what he believes the government ought to be doing anyway.

“If called, I will certainly serve,” he said. “But if not called, I will probably serve anyway.”