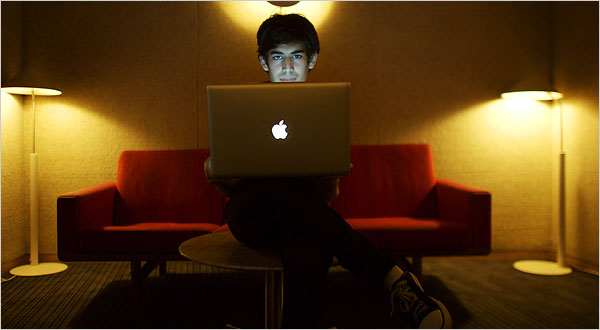

Short version of this story: Barrett Brown and Aaron Swartz filed a FOIA together on “persona management software” and here is the document that came back on that request.

Index of a few highlights of this document:

Page 1 – $2,760,000 bid

Page 3 – Explains what the software does

Page 4 – Explains the VPN and “user traffic mixing”

Page 4 – Explains Static IP Address Management

Page 5 – Explains “Virtual Private Servers”

Page 6 – Explains “Point of Presence Locations” to allow personas to appear to originate from different locations

Page 7 – Explains the “Secure Operating Environment”

Page 8 – Says $2,760,000 again

Detailed version of the story:

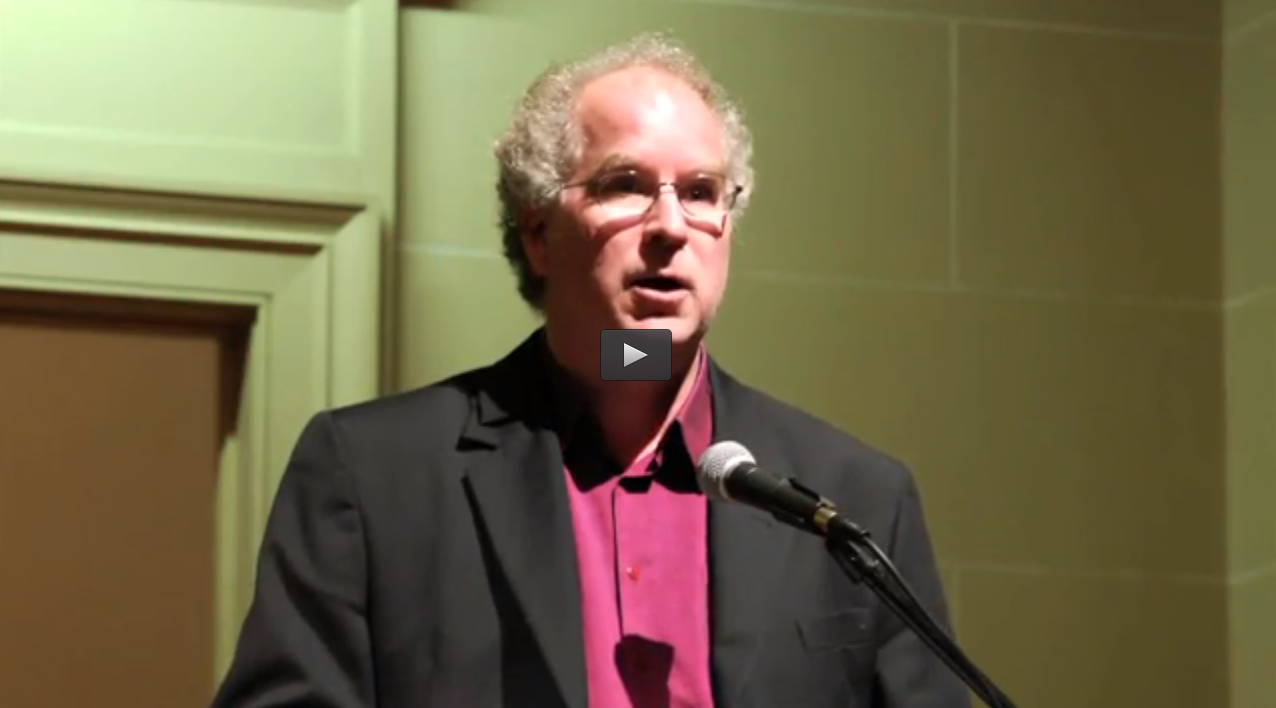

As I was preparing Barrett Brown and Trevor Timm’s segment from the Aaron Swartz Day Evening Event for publication, and transcribing some of it, I realized that he and Aaron had actually kinda known each other.

This was amazing to me, as I had asked Barrett to start participating in our last two years of Aaron Swartz Day’s because his projects had felt so on-target with Aaron’s concerns and values, not because I knew that they had ever exchanged emails, much less collaborated at any point.

Barrett himself had basically forgotten about it until recently at the end of his talk with Trevor Timm during last year’s Evening Event. As I was transcribing the talk last week, my ears perked up as Barrett explained their interactions:

“He (Aaron) once offered to do an FOIA request on persona management. One of my interests back then. One of these disinformation propaganda methodologies that have come out of the intelligence contract industries, and had been encouraged by various states. Something that I think is very dangerous. So he offered to do his thing on that. To explore the possibilities and see if we could get some information on it. And the interesting thing about that is that I’d sort of forgotten about it until very recently. I’m not sure where that was left. I’m not sure if he got some results back.”

Aha! The hunt was on – I wanted to find this request and find out what information ever came back for it. I still didn’t know what “persona management” was exactly, but I could guess the outcome – sock puppets. I had always known that sock puppets were very dangerous, from the first day I learned of their existence en mass.

I had been working with Muckrock intensely all week myself, filing dozens of public records requests to numerous police and sheriff departments for the Aaron Swartz Police Surveillance Project. (Which just revamped it’s Muckrock templates, by the way.)

I wrote Barrett an email immediately asking what ever came of it. He said, to his knowledge, it was filed, but he didn’t know if anything was ever sent back on it. He sent me this Project PM link on “Persona Management”:

Persona management on Project PM:

Persona management entails the use of software by which to facilitate the use of multiple fake online personas, or “sockpuppets,” generally for the use of propaganda, disinformation, or as a surveillance method by which to discover details of a human target via social interactions. Various incarnations of this capability have been discovered in the form of patents, U.S. military contracts, and e-mail discussions among intelligence contractors.

My first idea was to go back to the original story by Jason Leopold in Truthout that was published immediately after Aaron’s death. There was a link in it to all of Aaron’s FOIA requests, but it was broken. So I wrote Michael Morisy, founder of Muckrock, and asked him about it. He not only gave me a good link of every FOIA request Aaron Swartz ever filedand what he received back, on Muckrock. But he sent me the exact FOIA request in question, asking about persona management software. As well as the document that came back.

I sent the link to the response to Barrett.

He replied:

“Hey, I believe this is the same RFP that became public in 2011, though I’m not entirely sure. But yes, that’s exactly what it’s used for; social media accounts are the main vector, and as seen by the recent NYT story on the Israeli firm that Trump campaign approached regarding this, it’s definitely been marketed to entities as a means of influencing elections (in this case, influencing GOP delegates).” (I have reposted the NYT story on our blog .)

This software allows you to have sock puppets on steriods, provide VPNs for masking your geographical location, with the ability to actually pull in feeds from the geographical location you are claiming to be in, so you make the right comments and comment on local posts/issues and such.

Sock puppets and fake personas were not a new invention, of course. But you usually had to be a technical wizard of sorts to be able to pull it off. You would have to actually write things in a certain voice and monitor the input and output feeds of a given location on your own. Perhaps a gifted individual could have 5 or 10 of these going at once, but that would be impressive.

In contrast, using the software described in the RFP that was retrieved from Aaron’s FOIA request on Barrett’s behalf, someone could have dozens or even hundreds of these things going at once; without having to remember everything. In addition, the software could refresh one’s memory about a certain profile before having to interact with a human. And human interactions come so rarely anyway. Most all social media interactions are passive – like email, as opposed to conversations in real time.

From the NY Times story:

“A top Trump campaign official requested proposals in 2016 from an Israeli company to create fake online identities, to use social media manipulation and to gather intelligence to help defeat Republican primary race opponents and Hillary Clinton, according to interviews and copies of the proposals.

The Trump campaign’s interest in the work began as Russians were escalating their effort to aid Donald J. Trump…

The campaign official, Rick Gates, sought one proposal to use bogus personas to target and sway 5,000 delegates to the 2016 Republican National Convention by attacking Senator Ted Cruz of Texas, Mr. Trump’s main opponent at the time.” – NY Times Article by By Mark Mazzetti, Ronen Bergman, David D. Kirkpatrick and Maggie Haberman.

I will keep you posted as things develop.

Come discuss this and other Aaron Swartz Day mysteries at our March 8th Raw Thought Salon.

References:

- Persona Management listing on Project PM (courtesy of the Internet Archive): https://web.archive.org/web/20170326000753/http://wiki.project-pm.org/wiki/Persona_Management (http://wiki.project-pm.org/wiki/Persona_Management is temporarily down.)

- Document returned from Aaron’s “persona management” FOIA request : https://www.muckrock.com/foi/united-states-of-america-10/persona-management-software-544/#file-9522

- Every FOIA Aaron Ever Filed on Muckrock, https://tinyurl.com/Aaron-Swartz-FOIAs

- Aaron Swartz’s FOIA Requests Shed Light on His Struggle, By Jason Leopold, for Truthout, January 16, 2013 https://truthout.org/articles/cyberactivist-aaron-swartz-legacy-of-open- government-efforts-continues/

- Rick Gates Sought Online Manipulation Plans From Israeli Intelligence Firm for Trump Campaign By Mark Mazzetti, Ronen Bergman, David D. Kirkpatrick and Maggie Haberman for the New York Times, October 8, 2018 https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/08/us/politics/rick-gates-psy-group-trump.html