Here’s a clip from the film “The Internet’s Own Boy” – Directed by Brian Knappenberger – which explains the PACER project in more detail. [This is background for our Next Raw Thought Salon on March 8th.]

Clip on the Internet Archive

Clip on YouTube

PACER is the name of the website that lawyers use to retrieve legal documents from current and past court cases. These documents make up the precedents that make up “the law,” yet to access documents on PACER you must have a credit card and pay per page. (Costing a dime or more for *each* page, so you can see how it can add up quickly. )

You can understand why this “pay to see the law” system could present a problem for anyone who doesn’t have a credit card or is unfamiliar with the details of legal proceedings.

Aaron learned of a program which enabled free access to PACER via a small group of libraries across the country, and coordinated with a friend to download millions of PACER documents.

The FBI didn’t like it, and investigated him for a while, including surveillance at his parent’s home. But ultimately it had to let it go, because Aaron hadn’t actually done anything illegal.

Below is a transcription of the PACER Section of “The Internet’s Own Boy“ (Directed by Brian Knappenberger)

Brewster Kahle – Founder, Internet Archive:

“How can you bring public access to the public domain? It may sound obvious that you would have public access to the public domain, but in fact, it’s not true. So, the public domain should be free to all, but it’s often locked up. There’s often guard cages. It’s like having a National Park but with a moat around it and gun turrets pointed out, in case somebody might want to come and actually enjoy the Public Domain.

One of the things Aaron was particularly interested in was bringing public access to the public domain. It was one of the things that got him into so much trouble.”

Stephen Shultze – Former Fellow, Berkman Center for Internet and Society at Harvard:

“I had been trying to get access to Federal Court records in the United States. What I discovered was a puzzling system, called PACER, which stands for “Public Access to Court Electronic Records.

I started Googling and that’s when I ran across Carl Malamud.”

Narrative: “Access to legal materials in the United States is a 10 billion dollar per year business.”

Carl Malamud – Founder, Public.Resource.org

“PACER is just this incredible abomination of government services. Ten cents a page. It’s this most brain dead code you’ve ever seen. You can’t search it. You can’t bookmark anything. You’ve gotta have a credit card. And these are “public records.”

U.S. District Courts are very important. That’s where a lot of our seminal legislation starts. Civil Rights cases. Patent cases. All sorts of stuff. And journalists and students and citizens and lawyers all need access to PACER and it fights em every step of the way.

People without means can’t see the law as readily as people with that American Express card. It’s a poll tax on access to justice.”

Tim O’Reilly, Publisher

“The law is the operating system of our democracy, and you have to pay to see it? That’s not much of a democracy.”

Stephen Shultze: “They make about 120 million dollars a year on the PACER system and it doesn’t cost anything near that, according to their own records.

In fact, it’s illegal. The E-government Act of 2002 states that the courts may charge “only to the extent necessary” in order to reimburse the costs of running pacer.”

Narrator: “As the founder of Public.Resource.org, Malamud wanted to protest the PACER charges.

He started a program called “The PACER Recycling Project.” People could upload documents they had already paid for to a free database, so others could use them.”

Carl Malamud: “The PACER people were getting a lot of flack from congress and others about public access. And so they put together this system in seventeen (17) libraries across the country, there was free PACER access. That’s one library every 22,000 square miles I believe. So it wasn’t like really convenient.

I encouraged volunteers to join the “thumb drive core” and download docs from the public access libraries and upload them to the PACER recycling site. People take a thumb drive into one of these libraries and they download a bunch of documents and then send em to me. And it was just a joke. In fact if you clicked on “thumb drive core,” the Wizard of Oz, ya know, the munchkins singing, video clip came up.

But of course, I get this phone call from Steve Shultze and Aaron saying “Gee, we’d like to join the Thumb Drive Core.”

Stephen Shultze: “Around that time, I ran into Aaron at a conference. So I approached him and said “hey, I’m thinking about doing an intervention on the PACER problem.”

Narrator: “Shultze had already developed a program that could automatically download PACER documents from the trial libraries. Swartz wanted to take a look.”

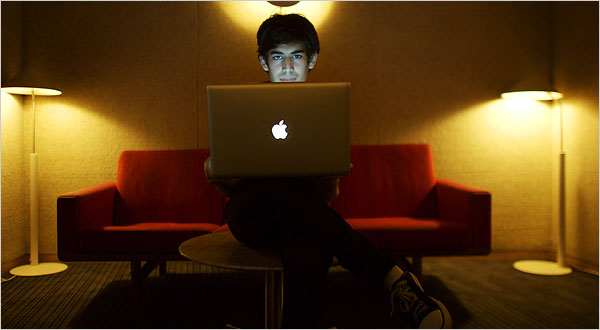

Stephen Shultze: “So, I showed him the code. And I didn’t know what would come next, but as it turns out, over the next few hours at that conference. He was off sitting in a corner, improving my code, recruiting a friend of his that lived near one of these libraries to go into the library and to begin testing his improved code, and at some point the folks at the court realized something’s not going quite according to plan.”

Carl Malamud: “And data started to come in, and come in, and come in. Soon there were 760 GB of PACER docs. About 20 million pages.”

Narrator: “Using information retrieved from the trial libraries, Swartz was conducting massive automated parallel downloading of the PACER system. He was able to acquire more than 2.7 million Federal Court Documents. Almost 20 million pages of text.

Carl Malamud: “Now, I’ll grant you that 20 million pages perhaps exceeded the expectations of the people running the pilot access project, but surprising a bureaucrat isn’t illegal.”

Aaron & Carl decided to talk to the New York Times about what happened.

They also got the attention of the FBI, who began to stake out Swartz’ parents’ house in Illinois.

Carl Malamud: “I get a tweet from his mother saying ‘Call me!’ And I’m like what the hell’s going on here? So, I finally got a hold of Aaron, and Aaron’s mother is like ‘oh my god FBI, FBI, FBI’ ”

Noah Swartz: “An FBI agent drives down our home’s driveway trying to see if Aaron is like, in his room. And I remember being home that day and wondering why this car was driving down our driveway and just driving back out. That’s weird. Like five years later I read the FBI file and I’m like my goodness – that was the FBI agent, in my driveway.”

Carl Malamud: “He (Aaron) was terrified. He was totally terrified. He was way more terrified after the FBI actually called him up on the phone and tried to sucker him in to coming down to a coffee shop without a lawyer. He said he went home and laid down on the bed, and was shaking.

Narrator: The downloading also uncovered massive privacy violations in the court documents. Ultimately, the courts were forced to change their policies as a result.

And the FBI closed their investigation without bringing charges.

Cory Doctorow: “To this day, I find it remarkable that anybody, even at the most remote podunct field office of the FBI, thought that a fitting use for taxpayer dollars was investigating people for theft on the grounds that they had made the law public. How can you call yourself a “law man,” and think there can possibly be anything wrong in this whole world with making the law public.”